Abstract

This article examines the strategic opportunities for enhancing India-Taiwan ties in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) amidst growing geopolitical tensions. Historically, a hub of maritime trade and contestation, the IOR has become increasingly important in global economic and security considerations. China’s rising influence in the region, coupled with India’s growing strategic and economic presence, has sparked competition for dominance, particularly in areas like energy security and control of the critical sea lanes. Taiwan, strategically located in the Western Pacific Ocean and dependent on energy imports via the Indian Ocean, also has significant stakes in the region. The article argues that India and Taiwan, while traditionally maintaining limited diplomatic and security ties, could benefit from an informal yet strategic partnership in the IOR. This collaboration could focus on maritime law enforcement, cyber-enabled maritime domain awareness, and addressing non-traditional security challenges, such as climate change and piracy. Additionally, areas such as the blue economy, semiconductor cooperation, and space collaboration present opportunities for mutual growth. The article suggests that, while formal security alliances may not be feasible due to the One-China Policy, India and Taiwan can still explore deeper cooperation through backdoor channels and Track 1.5 diplomacy, ultimately contributing to peace and stability in the broader Indo-Pacific region.

Introduction

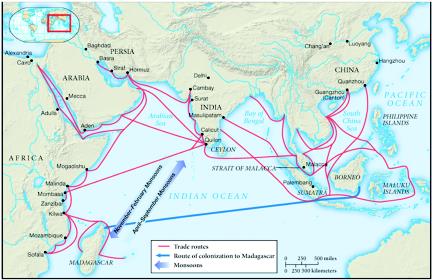

Even before the inclusion of the Indian Ocean in the lexicon of Asia-Pacific to become the new geopolitical construct called ‘Indo-Pacific’, the ocean has historically been a theatre of human interaction via maritime trade and a space full of contestation between regional and extra-regional powers. The third largest of the world’s five oceans, the Indian Ocean covers 68.556 million sq kms (CIA World Factbook)1 and it is one of the world’s key lines of communication which connects East to the West. It is both a critical global trade route and the source of more than 20 per cent of world petroleum exports.2 The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is extremely crucial as it is the most heavily trafficked and strategically important trade corridor, containing three of the world’s seven major maritime chokepoints: the Malacca Strait, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait. India is the key player situated at the crossroads of the Indian Ocean, however, India competes with China in the region. Due to its growing criticality for economic and geo-strategic reasons, the IOR has become an arena for competing influence and rivalry primarily between the United States (US), China, and India—summed up as Chinese pearls, US diamonds and Indian nuggets. This competition reflects concerns over energy security and secure access to Sea Lines Of Communication (SLOCs).

The Indian Ocean accounts for 50 per cent of the global container traffic. Additionally, 70 per cent of all petroleum product shipments transit through the Indian Ocean as they travel from the Middle East to the Pacific. 40 per cent of world trade passes through the Strait of Malacca; while the Strait of Hormuz sees 40 per cent of the world’s traded crude oil. 80 per cent of China’s oil and 65 per cent of India’s oil pass through the Indian Ocean. 90 per cent of India’s foreign trade by volume and 70 per cent by value are routed through the Indian Ocean, representing over a third of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For Taiwan, some 98 per cent of the energy is imported, and that import mix depends especially on fossil fuels, which comprise 93 per cent of Taiwan’s overall energy supply. Close to 76 per cent of Taiwan’s oil came from the Middle East in 2018.3 As of Sep 2019, Saudi Arabia alone accounted for some 30 per cent of crude purchases by Formosa Petrochemical4, one of Taiwan’s two leading oil refining companies. Since IOR is rife with traditional and non-traditional security threats, any slowdown or disruption in tanker traffic—whether from diplomatic standoff, piracy or war, could cripple these countries, sending global shockwaves. RD Kaplan, the American author, aptly argues that the “Indian Ocean will become ‘Centre Stage’ in the 21st Century, the place where many global struggles will be played out including conflicts over energy, clashes between Islam and the West, and rivalry between a rising China and India”.5

Map 1: Trade Routes Passing Through the Indian Ocean6

Indian Ocean Region Power Dynamics

In the context of the Asian century, the ‘Rise of China’ and ‘Rise of India’ have become commonly used. Although the exact levels of their power and whether they can be classified as ‘Great Powers’ may be debated, their relationship has become consequential for the region as they expand their geopolitical reach and compete for influence in the same geopolitical spaces of continental and maritime regions of South Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Geopolitics is important for understanding Sino-Indian dynamics.7 General geopolitical concept of great powers’, ‘Pursuit of primacy’ is in play between India and China, official rhetoric notwithstanding.8 Their pursuit of primacy lies and intersects in the same ‘Strategic Space’ of Asia-Pacific, South Asia and the Indian Ocean, where both the countries are thriving to assert their influence, authority and even hegemony.

The strategic location and economic potential of the IOR make it a volatile and troublesome region in the world. The growing influence of China in the region has led to emerging power dynamics in the region and a competition for influence, resources, and dominance, making this area one of the most dangerous conflict zones with the possibility of nuclearisation of the region. The IOR has historically been a critical theatre for engagement and interest for India, as it constitutes India’s immediate as well as extended neighbourhood, and has the potential to impact its security environment. India enjoys a strategically advantageous location in the Indian Ocean and considers itself a key regional and security player. Ensuring a secure and stable Indian Ocean is, therefore, central to India’s security and prosperity. The increasing Chinese belligerence in India’s neighbourhood, both maritime and territorial, has engendered new security challenges for India which requires an ‘Out-of-box’ approach.

It is evident from China’s behaviour that its expansion as a great power is global, not limited to the Eastern Pacific, Taiwan, and the South China Sea. China’s maritime renaissance and its ‘Oceanic Offensive’, drive for a blue-water fleet and Mahanian view have brought her into the Indian Ocean after more than five centuries. Since 2008, Chinese flag has been ubiquitous in IOR and this time China intends to stay. There is an overlap of contestation for primacy, power, prestige, influence, authority, and even hegemony between India and China, as both strive to stamp their authority on the same region, the same spatial arena—and in Asia, the interests of both India and China intersect9 in the IOR. The two nations share the same strategic space and a new ‘Great Game’; geopolitical rivalry, seems to be at play between these two rising powers, likened to 19th Century geopolitical rivalry between Russia and British Empire. The general theme underlying this concept is competition for influence, whether at political, economic or cultural levels, quite visible in the IOR. China’s increasing presence10, not just in terms of naval vessels in the IOR, but also in the IOR countries like Maldives and Sri Lanka (under the Belt and Road Initiative [BRI]), its investments, use of United Public Front Department in India’s neighbourhood to exert influence, or create favourable public opinion is a cause for concern. The recent spat between India and Maldives (anti-India vs pro-China narrative) is one such example.

Map 2: China’s BRI11

However, there is a key geopolitical distinction between the original great game (between Russia and the British Empire) and the new great game (India and China). The former was primarily land-based, focusing on the overland threat to the British India from Central Asia, whereas, the latter has an oceanic dimension. It evokes the Mahanian concept of ‘Sea Power’ and control of ‘SLOCs’. Alfred Thayer Mahan predicted in 1897, “Whoever controls the Indian Ocean will dominate Asia. This ocean will be the key to the seven seas in the 21st Century. The destiny of the world will be decided on its waters”, and rightly so.

The sea-based component of the BRI, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road serves as a tool in China’s grand strategy. It has economic (development of USD 1.2 tn blue economy), military (place-and-base approach for permanent access to the Indian Ocean), and political dimensions (enhancing China’s international discourse power). It challenges India’s own SLOCs and its general influence in the region. China is trying to build resilience to economic or diplomatic isolation that could negatively impact its economy and subsequently its domestic stability.12 India, on the other hand, has pronounced its vision for the Indian Ocean thorough Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR)13 and its maritime ‘Panchamrit’ or five-fold framework for India’s engagement in the IOR14 and the idea of a Blue Revolution. India’s trade and economic relations with East Asia are acquiring greater weight and Delhi’s stake in the political stability and security of the Western Pacific has steadily grown. China’s increasing reliance on the Indian Ocean and the acceleration of India’s economic growth and strategic interests in the Pacific appear to intersect, and Taiwan cannot be ignored in this dynamic.

Situating Taiwan in the Indian Ocean Region dynamics

Situated in the Western Pacific between Japan and the Philippines, at the junction of the East and South China Seas, around 4,580 nautical miles from the Port of Diego Garcia (considered to be the middle of the Indian ocean), and 4,729 nautical miles from the Port of Mumbai, Taiwan also has considerable stakes in the Indian Ocean as one of the world’s largest distant-water fishing fleets. It is the world’s sixth largest fishing nation in terms of hauls from international waters and it catches more albacore tuna in the Indian Ocean than any other nation. The annual catch by Taiwanese fishing boats operating in the Indian Ocean is estimated to be around 17,000 metric tons. It adds to the blue economy of Taiwan which constituted approximately 3.3 per cent of its annual GDP in 2019.15

Despite China’s steady strategy to isolate Taiwan diplomatically and constrain its international space, Taiwan has managed to remain internationally relevant. Its international stature has increased, contrary to Chinese attempts to demoralise it by strangulating it diplomatically. The most recent instance of diplomatic poaching was that of the Pacific island nation of Nauru, just two days after the Jan 2024 Presidential elections, which gave mandate to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) for the third time in a row. China considers DPP secessionist and has warned of consequences if it wins the election. China maintains that Taiwan is a renegade province that must be reunified with the mainland and under Xi’s national rejuvenation dream, China asserts that it can use force to achieve reunification with Taiwan, if necessary.

Map 3: Strategic Location of Taiwan16

Interestingly, Taiwan entered into an official relationship with Somaliland, another country that remains unrecognised by most of the world. Dr Mohamed Hagi, the Chief Representative of the Republic of Somaliland Representative Office in Taiwan, draws parallels between the geopolitical realities of Somaliland and Taiwan, such as their non-affiliation with multilateral organisations like the United Nations or the lack of diplomatic recognition.17 However, he claims that both Taiwan and Somaliland still exert significant influence within and beyond their borders. This move was inspired by the TAIPEI Act (2020), introduced by the US to encourage nations to strengthen their ties with Taiwan. This relationship has economic, political, and strategic dimensions. It provides an opportunity for Taiwan to expand its influence and tap into the growing markets in Africa.18 With this, Taiwan formally re-entered the IOR after more than two decades, following the end of formal diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia (1990) and South Africa (1998). Situated in East Africa, Somaliland’s strategic geographical location offers Taiwan the potential to establish a ‘Forward Base’ either for diplomatic or strategic purposes (Jacob and Liu 2020).19 The port of Berbera in Somaliland is located just 250 km southeast of Djibouti, where China has established its naval base, further intensifying the regional security dilemma.

However, the question remains whether Taiwan has the capability to achieve this outcome and whether India can assist Taiwan in its quest in any meaningful way? Taiwan may have the intent to undertake this ambitious project but lacks the capability. India, on the other hand, has the capability but lacks the intent to enter into any formal or diplomatic arrangements that may be perceived as provocative or contrary to the One-China Policy. The security facet of India-Taiwan relations is a significant ‘No’, yet, the existence of informal and unofficial exchanges under the radar cannot be ruled out. This is evident from the increasing prominence of the Taiwan Strait security situation in Indian strategic and military circles. In late Jul 2023, India’s Chief of Defence Staff, General Anil Chauhan, ordered a study group to assess India’s possible options if Taiwan were to be attacked by China.20 The idea was to develop a Taiwan contingency plan. This was ordered during a conclave of senior military commanders with an objective to prepare contingency plans in the event of a conflict over Taiwan. Obviously, the Indian defence and strategic community has been deliberating about Taiwan’s security and its possible fallout for India, which underscores the need for increased India-Taiwan security information sharing, potentially facilitated through a third party.

In another significant gesture, former Chiefs of India’s three military branches—former Air Chief, RKS Bhadauria, former Naval Chief, Karambir Singh, and former Army Chief, MM Naravane—participated in the Ketagalan Forum on Indo-Pacific Security Dialogue in Taipei in Aug 2023. Admiral Singh was among the key speakers at the event. He categorically mentioned during his speech that India does not want South China Sea playbook of the People’s Republic of China to be replicated in the IOR.21 This marked the first occasion on which three ex-tri-service chiefs were present in Taiwan simultaneously, and they also took part in closed-door discussions at the Institute for National Defense and Security Research (INDSR), a think tank operated by Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Although they maintained that they were not part of any study group and were visiting Taiwan in a personal capacity, their presence in Taipei provoked significant fury in China. Various table top exercises simulating Chinese attack on Taiwan are organised regularly in Taiwan, the US and Japan to prepare for a Taiwan contingency, however, in May 2023, Indian military think tank, United Services Institution of India22, in collaboration with the INDSR, held workshop in New Delhi simulating the potential effects of tensions in the Taiwan Strait on the Sino-Indian border. The panel, which included experts from Taiwan and the US, deliberated upon the likely scenario in broader Indo-Pacific Region with a focus on Taiwan Strait and possible implications for India. Similar exercises in India cannot be ruled out, highlighting the seriousness of Taiwan’s security issue for India’s own security and military calculations. This points out the seriousness of Taiwan security issue for India’s own security and its military calculations. Such interactions at Track 1.5 diplomacy have become a regular feature in India-Taiwan relations.

Conclusion

India and Taiwan, two vibrant democracies in the Indo-Pacific region, maintain limited diplomatic and security cooperation. Their relationship has been largely transactional: India views Taiwan as a source of Mandarin expertise and intelligence on China, while Taiwan seeks to tap into India’s vast market and diplomatic influence. Although economic, educational, and people-to-people ties have grown over the past decade, India’s delicate and critical relationship with Beijing significantly influences its engagement with Taiwan. However, China’s aggressive foreign and economic policies, coupled with security concerns for both India and Taiwan, necessitate a re-evaluation of India’s traditional stance and the exploration of innovative engagement strategies that avoid antagonising China.

The evolving power dynamics in the IOR present opportunities for enhanced India-Taiwan cooperation, fostering a coherent Indo-Pacific framework. Both nations, given their geostrategic locations, have the potential to collaborate with regional and extra-regional actors to address mutual interests and challenges. Taiwan’s compatibility with such an approach is evident, especially in light of global geopolitical uncertainties, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and the Israel-Hamas conflict. These events have plunged the world into flux, amplifying concerns about China’s potential annexation of Taiwan, inspired by Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

The global geopolitical divide increasingly contrasts a rule-based liberal democratic order, led by the US, with an authoritarian bloc championed by China and Russia. India and Taiwan, aligning with the democratic bloc, share economic and security concerns as well as untapped potential for collaboration. Their respective Act East and New Southbound policies converge significantly, particularly in maritime spaces within the IOR. Cooperation could encompass maritime law enforcement, advocacy for freedom of navigation, and addressing non-traditional maritime security threats. Taiwan’s expertise in blue economy activities, such as aquaculture, aligns with India’s SAGAR vision and Amrit Kaal (Golden Era) Vision 2047, creating mutual opportunities for growth.

On a tactical level, cyber-enabled technologies for maritime domain awareness and India’s support for Taiwan’s inclusion in the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) are promising areas of collaboration. Taiwan’s proven track record in maritime safety, fisheries management, science, trade, disaster risk management, and tourism underscore its value. India’s advocacy for Taiwan in IORA, despite past hesitations, could strengthen the Indo-Pacific architecture without framing it as an anti-China strategy.

The dynamic maritime space of the IOR offers a platform for both traditional and non-traditional security collaborations. India-Taiwan ties could encompass addressing climate change, ensuring technological and economic security, and countering Chinese aggression. Recent developments, such as supply chain disruptions, the Galwan Valley clash, and potential semiconductor collaborations, provide fresh momentum to bilateral ties. Taiwan’s intelligence on Chinese naval activities, shared through the US and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue frameworks, is particularly valuable. Similarly, India’s insights into Russian arms systems could aid Taiwan in preparing for potential conflicts with China.

The India-China rivalry, coupled with Russia’s role as a major arms supplier to both nations, further complicates regional dynamics. Nonetheless, private-sector cooperation in military vessel and aircraft maintenance between India and Taiwan remains feasible. A stronger Indian presence in the IOR benefits Taiwan strategically, as does potential Taiwanese participation in the Indian Navy’s Information Fusion Centre for the IOR.

India’s evolving approach toward China is evident in measures such as renaming Tibetan locations and signing a labour agreement with Taiwan, signalling a subtle shift in its policy. These actions pave the way for deeper people-to-people connections and economic engagement, setting the stage for enhanced security cooperation.

India and Taiwan can innovate and expand their partnership in areas such as search and rescue at sea, combating illegal fishing, maritime domain awareness, counterterrorism, counter-piracy, human trafficking, cybersecurity, space cooperation, and technological development. Semiconductor manufacturing remains a priority, but other sectors, such as electric vehicles, healthcare, food processing, and aquaculture offer immense potential. Leveraging Taiwan’s expertise in these areas aligns with India’s developmental goals, including the Blue Revolution under SAGAR.

The convergence of India’s Act East Policy and Taiwan’s New Southbound Policy provides a robust framework for collaboration in these areas, fostering peace, security, and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

Endnotes

1 “The World Factbook- Indian Ocean”, Central Intelligence Agency, Accessed 09 Oct 2024,

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/about/archives/2023/oceans/indian-ocean/.

2 Anthony H Cordesman and Abdullah Toukan, “The Indian Ocean Region: A Strategic Net Assessment”, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Aug 2014, 6-7,

https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/140725_Indian_Ocean_Region.pdf.

3 Feigenbaum, E. A., & Hou, J. Y. (2022), ”Overcoming Taiwan’s energy trilemma”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

4 Ibid

5 Kaplan, R. D. (2011), ”Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the future of American power”, Random House Trade Paperbacks.

6 “Early Maritime Relations of Kollam”, Kerala Museum, accessed 20 Dec 2024,

https://keralamuseum.org/early-maritime-relations-of-kollam/

7 Scott, David, “The great power ‘great game’ between India and China: ‘The logic of geography’”, Geopolitics 13, no. 1 (2008): 1-26.

8 Agnew, John, “Geopolitics: Re-envisioning World Politics”. London: Routledge, 1995.

9 Saran, Shyam, “Present Dimensions of the Indian Foreign Policy”, Address at the Shanghai Institute of International Studies, Shanghai, 11 Jan 2006, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India,

https://www.mea.gov.in/incoming-visit detail.htm?2078/Present+ Dimensions+of+the+Indian+Foreign+Policy++Address+by+Foreign+Secretary+Mr +Shyam+Saran+at+Shanghai+Institute+of+International+Studies+Shanghai.

10 Deep Pal, “China’s Influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and resilience in Four Countries, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 13 Oct 2021,

https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/10/chinas-influence-in-south-asia-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries?lang=en

11 Jethro Jeff, “The Fate Of Chinas Belt And Road Initiative”, Jethro Jeff, accessed 20 Dec 2024,

https://jethrojeff.com/

12 Ghiasy, Richard, Fei Su, and Lora Saalman. “The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: Security Implications and Ways Forward for the European Union”, Executive Summary, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2018,

https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/the_21st_century_ maritime_silk_road_executive_summary.pdf

13 “Prime Minister’s Remarks at the Commissioning of Offshore Patrol Vessel OPV Barracuda in Mauritius”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 12 Mar 2015,

https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/24912/prime+ ministers+remarks+at+the+commissioning+of+offshore+patrol+vessel+ opv+barracuda+in+mauritius+march+12+2015

14 Ministry of Defence, “Maritime Cooperation with Regional Partners”, 21 Mar 2022,

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1807607

15 Tsai, Ching-Piao, “Blue Economy: A Spotlight on Taiwan”, Impact: The Economist. Accessed 03 Jul 2024,

https://impact.economist.com/ocean/sustainable-ocean-economy/blue-economy-a-spotlight-on-taiwan.

16 Peter Harris, “U.S. should accept that its Indian Ocean base belongs to Africa”, Nikkei Asia, 06 Feb 2023,

https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/U.S.-should-accept-that-its-Indian-Ocean-base-belongs-to-Africa

17 Mohamed Hagi, “A Future Outlook: Prospects for Somaliland-Taiwan Relations”, Global Taiwan Institute, 01 May 2024,

https://globaltaiwan.org/2024/05/a-future-outlook-prospects-for-somaliland-taiwan-relations/.

18 Ibid

19 Jacob, Jabin T., and Roger C. Liu. “Returning to the Indian Ocean: Maritime Opportunities Arising from Taiwan’s New Ties with Somaliland”, National Maritime Foundation, 22 Jul 2020,

https://maritimeindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Jacob-Liu-Taiwan-Somaliland-21-July-2020.pdf

20 Nitin A. Gokhale, “Indian Military Weighs Options In Case China Attacks Taiwan Strait”, News Global, 07 Aug 2023,

https://stratnewsglobal.com/world-news/indian-military-weighs-options-in-case-china-attacks-taiwan/

21 Author also participated in this forum and later interviewed Admiral Singh and General Naravane.

22 Workshop On ‘Evolving Global Scenarios In Context Of Ongoing Dynamics In The Indo-Pacific Region’ organised by the United Service Institution of India on 14 May 2024,

https://www.usiofindia.org/events-details/WORKSHOP_ON_EVOLVING_ GLOBAL%20SCENARIOS_IN_CONTE XT_OF_ONGOING_DYNAMICS_ IN_THE_INDO_PACIFIC_REGION.html

@Dr K Mansi is an Assistant Professor at Amity University, Haryana, and serves as the Deputy Director of the Indo-Pacific Studies Centre. She is also an Honorary Research Associate at Murdoch University, Australia, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Taiwan Centre for Security Studies, Taiwan.

Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CLIV, No. 638, October-December 2024.

Author : Dr K Mansi

Category : Journal

Pages : 613 | Price : ₹CLIV/638 | Year of Publication : October 2024-December 2024