Abstract

This article attempts to identify the key forces in the tumultuous province of Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), which historically was part of the undivided India’s Jammu and Kashmir region, but has been illegally usurped by Pakistan (after the 1948 War), and has since undergone unprecedented changes, especially since the passage of the ‘New Governance Order of 2009’. Pakistan, India, the erstwhile Great Britain, China, Russia, and Afghanistan are the key players having presence in GB. In this article, each is first analysed in detail, with historical roots and geo-political significance explored, leading to an understanding of the routes. The role of erstwhile British rulers, to whom it was leased, and their Russian connection, as well as governance under the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who had annexed it, is also briefly examined. Next, the article enumerates why international focus remains on this part of the globe, and how and why Pakistan still continues to exploit its people and their resources, partially leasing the region to China (for the gains of the lucrative China-Pakistan Economic Corridor). Lastly, the article analyses how India can play a constructive part in getting GB and its people their due in deciding their future; whether as an Autonomous Unit, a sovereign Independent State, or reunite with Kashmir. Herein, lies the role of India—maybe after its own Kashmir conundrum is resolved peacefully, the process which has started after the successful installation of an Omar Abdullah-led government. But for this, a fresh approach is needed, minus the baggage of a conflict-ridden history. In conclusion, multiple options and scenarios for a peaceful and prosperous future of this resource-rich province are offered, with India’s help/intervention, supported by international players (mainly the United States and Europe), thus preventing Pakistan from legitimising its continued illegal control over GB.

Introduction

Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), a strategically located province in the far- north of Pakistan, consists of 10 districts, a population of 2 million, and an area of 73,000 sq km. It shares boundaries with Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor, China’s Xinjiang Region, India’s Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), and Pakistan’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, as well as Pakistan-controlled swathe of territory in western Kashmir, referred to as ‘Azad Kashmir (AK)’.1

With the beginning of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan in 1947, both AK and GB came under the control of the latter. Pakistan then maintained an almost watertight division between the two regions: One could almost say that Pakistan established a kind of second ‘Line of Control (LoC)’, between AK and GB, beside the LoC that separates Pakistan from the Indian-administered parts of J&K. Recently, however, opposing political groups from both AK and GB have questioned Pakistan’s control over these territories, and have attempted to overcome the division, to establish political cooperation between the parts.

History

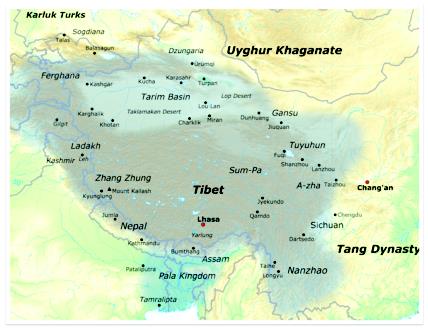

Map 1: Map of Tibetan Empire citing areas of Gilgit-Baltistan as part of its Kingdom in 780–790 CE

Source: Rootshunt2

Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan in the framework of Pakistan3

The state of J&K was created as a result of the Treaty of Amritsar signed between the British government and Gulab Singh in 1846. This treaty established Singh as the ruler of the new state and ushering in the Dogra rule. After 1947, it was divided into three parts. Two of them, AK and GB, are controlled by Pakistan, and the third is under Indian control.

Gilgit-Baltistan as Part of Pakistan

Between 1947 and 1970, the Pakistan Government established Gilgit Agency and Baltistan Agency. In 1970, the Northern Areas Council was formed by Pakistan’s ninth Prime Minister (PM), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Thus, the region was directly administered by the Federal Government and called Federally Administered Northern Areas. In 1963, Pakistan ceded part of Hunza-Gilgit, called Raskam, and the Shaksgam Valley of Baltistan region, which resulted in the Pakistan-China Border Agreement, 1963, over pending settlement of the dispute over Kashmir. This area is also known as the Trans-Karakoram Tract. The Pakistani parts of Kashmir to the north and west of the ceasefire line established at the end of the Indo-Pak War of 1947 (LoC, as it came to be called) were divided into Northern Areas (72,971 sq kms) in the north and AK (13,297 sq kms) in the south.4

Gilgit-Baltistan’s Self-Governing Status of 2009

On 29 Aug 2009, the Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order5 was passed by Pakistan, granting self-rule to GB by creating, among other things, an elected legislative assembly. This order uplifted the self-identification of this territory’s inhabitants through the name change, but left the region’s constitutional status within Pakistan undefined. Though its people now had Pakistani passports and identity cards, they were still not represented in Pakistan’s Parliament. However, for the first time, the people of GB gained the right to indirectly elect their own Chief Minister. The ordinance of 2009 not only gave GB a province-like status, but also granted locals some control over the budget and the right to legislate on 61 subjects, provided it did not violate the Constitution of Pakistan.

Influence of Foreign Powers in Gilgit-Baltistan

GB has a long history of being controlled by foreign powers. The people of the region—the Dards—are mentioned by classical Greek and Roman historians as well as in sacred Hindu texts. The early history (3rd Century CE–10th Century CE) of the region shows it being ruled by the Kushan, Chinese, and Tibetan empires. In the 7th century accounts of Chinese travelers, and 8th and 9th century Arabic and Persian chronicles, the region is referred to as Bolor in Arabic. It is also mentioned in the 10th Century Persian chronicle Hudud al-‘alam, the 11th Century Kashmiri classic Rajatarangini, and the 16th Century Tarikh-e-Rushdi of Mirza Haider Dughlat, a chronicler of the Mughal emperor Akbar’s court.6

Sikhs-Dogras-British

The colonial history of GB begins with forays of Dogra generals. In 1846, the British defeated the Sikhs and carved out a new princely state of J&K, with appointing the Governor of Jammu, Raja Gulab Singh, as its Maharaja. This history of foreign invasions and local rebellions lies at the heart of the confusion that surrounds the legal, political, and constitutional status of the region to this day. The successive invasions of local Rajas from Jammu and later from Kashmir, followed by the British, and the region’s attachment to Pakistan have resulted in multiple claims and counterclaims of sovereignty.7

In GB, there has always been a considerable indigenous resistance against all colonial powers. The legend of Gohar Aman, a ruler from Yasin who fought against the intruding Sikh and Kashmiri armies, remains alive to this day. The Genial Revolution of 1951 is another example, during which local people were killed while demanding their rights. Today, many people of GB make efforts to claim their rights against the control of Pakistan over the region. The Pakistani state is primarily represented in GB by the military and bureaucracy, which symbolise the concentration of power among lowlanders and foster a sense of disenfranchisement and lack of control over local affairs among the people.

As for British control, it lasted exactly 101 years, ending in 1947 with the partition of the Indian subcontinent. This control was primarily exercised through a proxy system, with a nominated ‘Political Agent’. These agents were typically individuals who had been posted in the region for an extended period and, as a result, understood the local politics and dynamics.

Afghanistan

Historically speaking, both Gilgit and Baltistan have their own local ethnic groups similar to other Dardic groups of eastern Afghanistan and the Khyber region, such as the Nooristani and Chatraili, etc., and have a different origin from the Indo-Aryan (with minor Dardic influence) Kashmiris. The region is also situated right next to Khyber and Wakhan corridor of Afghanistan. Even in the Islamic period, Afghans ruled both GB and Kashmir, and migrated to this region in large numbers.

Historically, many historians included GB within Afghanistan or the Land of Eastern Iran. The dream of ‘Greater Afghanistan’ of some nationalists led to a close relationship with the Soviets (to counter the ‘Occupying’ Pakistanis), ultimately resulting in the Soviet invasion and indirectly triggering the subsequent war and chaos. Immediately after Pakistan emerged as an independent nation in 1947, Afghanistan had demanded the creation of an independent ‘Pashtunistan’, or ‘Land of Pashtuns’. The idea was that Pakistan should allow the Pashtuns in the northwestern part of their country to secede and become an independent state if they so choose. Though the size of the envisioned Pashtunistan differed over time, Afghanistan’s proposals often encompassed about half of West Pakistan, including areas dominated by Baluch majorities.8

From a legal perspective, Afghanistan’s claim regarding the illegitimacy of its border with Pakistan was rather weak. Though Afghanistan claimed that the border had been drawn under duress, it had, in fact, confirmed the demarcation of this international frontier on multiple occasions, including agreements concluded in 1905, 1919, 1921, and 1930. However, the weakness of Afghanistan’s legal case was overshadowed by the historical connection it felt to the Pashtun areas and the strategic benefits it would derive from expanding its territory.

Amid Pakistan’s failure to stop the resurgence of Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, following the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in Aug 2022, GB is witnessing a growing influence of the Taliban. From burning down girls’ schools to kidnapping government officials, the oppression seems unending. Locals also recall that in 2018, miscreants had set 13 girls’ schools on fire across the district, but the government did not take any action even then. Taliban is against any progressive activities of women, enforces sharia law and engages in violent acts to assert its relevance. Sadly, the Pakistan administration is unable to control it.

Russian Influence

The Anglo-Russian agreement of 1873, which mutually defined the British and Russian spheres of influence in Central Asia and Afghanistan were mutually agreed upon, instead of ushering in a new era of cordial relations between the two rival powers, added new dimensions to the ‘Great Game’. While this agreement effectively legitimised the two sides’ advances to their advance within their respective zones, it also introduced the new challenge of delimiting the Afghan, Chinese, and Russian frontiers in the upper Oxus region of the Pamir mountains.

British attention was drawn to the complexity of this question by British officers who, in 1874, explored the Wakhan and Pamirs area. They discovered that Afghan territory in the eastern extremity extended to both sides of the River Oxus, which, under the 1873 agreement, had been declared to be the dividing line between Afghanistan and Russia. This discovery challenged the very foundation of the accord. On examining the passes of the Hindu Kush, British explorers found them easy to cross, making India vulnerable to attack from across the Hindu Kush passes, British explorers found them easy to cross, thus making India vulnerable to attack from across the Hindu Kush. Both these discoveries were strategically significant, leading the British to modify their frontier policy accordingly. The deputation of Biddulph in 1876 to survey the Hindu Kush passes, followed by the establishment of the British agency in Gilgit under the same oûcer in 1877, reflected the new British strategy to address the challenge posed by the Russian advance toward the Pamirs. Today, however, Russian influence in GB has declined and remains very limited, primarily centred.

American Influence

Initially, the sole focus of the United States (US) in the northern areas was to keep the Soviets at bay from Afghanistan. This led to the Great Afghan War, fought from 1979 to 1989, whose aftereffects included the breakup of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics into 15 independent republics. Later, at the beginning of the 21st Century, the events of 9/11 in the US profoundly influenced developments in South and Central Asia. Afghanistan and Pakistan became deeply embroiled in the US’ ‘War on Terror’ following the ouster of the Taliban regime from Kabul in 2001. The US-Afghan and Pakistan relations became a pivotal triangle in the strategic picture of South, Central and West Asia.9 However, following the US’ ignominious exit from Afghanistan in 2022, its influence over Afghan affairs and relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan have deteriorated, particularly after Pakistan expelled nearly 1.5 million Afghan refugees.

China and the Pak-China Nexus

The Karakoram Highway (KKH). The areas of the GB region were virtually disconnected from the rest of Pakistan until the completion of the KKH in 1978, which connects Pakistan with the Chinese province of Xinjiang via GB. Its construction was a landmark for the strategic friendship of Pakistan and China and its construction marked a significant milestone in the strategic friendship between Pakistan and China, and its impact on life in GB has been immense. For the government of Pakistan, these roads were crucial for connecting with this geographically and strategically important region. Today, China’s ambition to access the Gwadar deep-water port on the Baluchistan coast from its western provinces makes the KKH important for bilateral trade between Pakistan and China, and for their long-standing strategic friendship.11

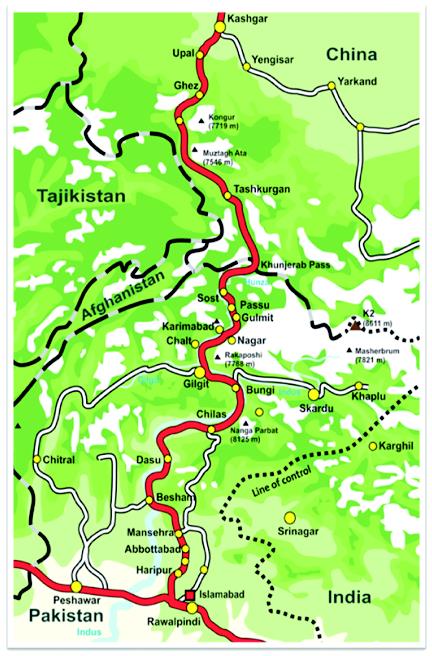

Map 2: The Karakoram Highway

Source- Rootshunt10

The construction of the KKH, followed by the development of other roads, has greatly transformed life in the area. The exchange between the mountain regions and down-country Pakistan, in terms of both the travel of people and the transport of goods, has increased significantly. Theoretically, KKH is an all-season and all-weather road. In practice, however, it is frequently disrupted by both natural and political events.

Over the last four decades, GB has been transformed from a remote, agricultural mountain area to a highly literate rural society, with the urban hub of Gilgit now connected to the markets of Pakistan and China via the KKH. This shift is a major game changer for its locals and a hot topic of discussion among foreigners and researchers.

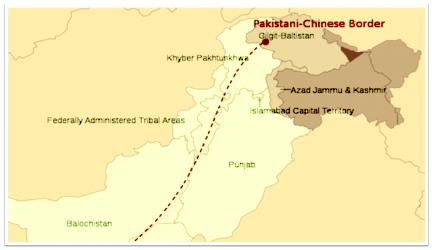

Map 3: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Source: CPEC Website12

The China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).13 The USD 46 bn CPEC is a network of highways, railway lines, oil pipelines, electrical power grids, fibre optic cables, and Special Economic Zones (SEZs), linking the Chinese trading hub of Kashgar in Xinjiang province with the Pakistani port city of Gwadar, located near the strategic Strait of Hormuz. However, the project has encountered significant challenges, with massive protests erupting in the GB region.

As in Baluchistan, where Gwadar is located, residents of GB are not opposed to the project itself but fear being excluded from its benefits. Although GB plays a key role in the CPEC project—with all roads and pipelines crossing into China from Pakistan passing through this mountainous region—not a single SEZ is being set up there. Consequently, calls for the rollback of CPEC and the withdrawal of Pakistani security forces from GB are growing louder.

In addition to GB’s disputed status, its undefined relationship with Pakistan further complicates the situation. At international forums, Pakistan maintains that GB is part of the dispute with India over Kashmir and that its future should be decided through a plebiscite, as outlined in United Nations resolutions. Hence, it has not been made a part of Pakistan and is not mentioned in the Pakistani constitution. Its people are neither conferred Pakistani citizenship nor allowed to vote in national elections, and they have no representation in Pakistan’s parliament. Although a legislative assembly was created in 2009, it is the Federal Government that wields real power in the region. Thus, Pakistan is not only forcibly occupying GB but also lacks the legal justification within its own constitution, putting its position in jeopardy.

Additionally, the presence of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army in GB constitutes the direct involvement of Beijing in the dispute over Kashmir, making any future understanding between Pakistan and India more difficult, and one that can arouse a new and serious rift between New Delhi and Beijing. The deployment of Chinese soldiers on Pakistani soil is, therefore, far from an ordinary matter. If successive Pakistani governments have consistently objected to the presence of the US troops in the country, why is there such openness towards the Chinese army?

Saudi-Iranian Influence

Some other factors have also affected life in GB, primarily contributing to deep-rooted sectarian violence. These include the proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran on Pakistani soil, the strategic location of GB as part of the disputed territory between Pakistan and India, and its proximity to China’s border. Religious and sectarian identities in GB have become dominant since the 1980s, coinciding with the peak of the Iranian Revolution and the Saudi Arabian government supported the establishment of madrassas across Pakistan in order to support Sunni Islam.14 The rise of sectarianism in Pakistan, particularly in GB, is closely linked to the backing provided by Iran and Saudi Arabia to their respective groups.

Indian Influence and Likely Future Role in Gilgit-Baltistan

By virtue of its geography, GB holds great strategic significance for India, as it is the only land link between Pakistan and China, and between China and India. India claims this territory and accuses Pakistan of illegally occupying it. Complicating Pakistan’s troubles with GB is India’s claim to this region, which has lately been articulated more robustly.15 Indian PM Narendra Modi made an oblique reference in his 2016 Independence Day speech to the grave human rights situation in Baluchistan, GB and other areas of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). A few days earlier, he had emphasised the need to highlight the plight of people in these regions at international forums. The Modi government can be expected to step up efforts to engage with Baluchi nationalists in the coming years and to assert its claims over GB more vigorously. Unsurprisingly, China and Pakistan are concerned. Will India’s stirring of the bubbling cauldrons in Baluchistan and GB exacerbate the security situation there? More importantly, what will happen to Pakistan’s already tenuous and illegal control over GB?

Likely Future Linkages. With regard to improving Indo-Pak relations, trade linkages have been operational since 2008, connecting the Indian-administered and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Consequently, the call for opening GB’s borders has gained momentum in recent years. The idea for the connection dates back to the 1990s, when a feasibility survey confirmed the project’s viability. Then, in 2011, the GB Legislative Assembly adopted a resolution towards establishing a 220 km-long road from Ghizer (westernmost district of Gilgit) to Tajikistan. The route would connect GB to Central Asia, through the Wakhan Corridor.16

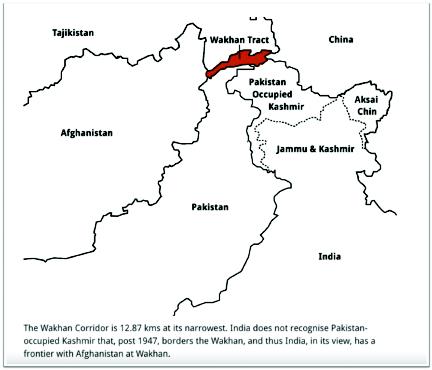

Map 4: Wakhan Corridor

Source: Centre for Land Warfare Studies17

Currently, this corridor lacks reliable connectivity. Due to its remoteness and sparse population, Wakhan has thus far evaded Taliban influence. But its inhabitants remain deprived of essential services. The time is ripe for India to lead investment to upgrade the physical and social infrastructure in the Wakhan corridor. This would only be feasible if connectivity is established between Gilgit and Wakhan, and GB’s borders are opened to allow India direct access to Wakhan. This proposed Gilgit-Wakhan route can also serve as the shortest route from Kashmir to Tajikistan.18

On the Indian side, linkages still exist between Ladakh and GB via the Kargil-Skardu road, Turtuk-Khaplu road, and Gurez-Astor road. These three routes were specifically proposed by the Prime Ministerial Working Group formed during PM Manmohan Singh’s regime in 2006. In particular, upgrading the 150 km Kargil-Skardu Road to an all-weather road would ensure year-round connectivity with GB, serving as a substitute for the Khunjerab link during winter months and providing a reliable route in case of natural disasters.

Despite the potential gains from stronger connectivity between South and Central Asia, challenges remain. The landscape of Ladakh is heavily militarised due to significant military deployments and tensions along the Line of Actual Control (the de facto India-China border) remain unresolved. In addition, the northwestern part of GB that borders the Wakhan Corridor faces topographical and environmental challenges from the mountain ranges and the snow-laden passes, and political challenges from the complexity of Af-Pak relations.19

However, given the state of bilateral relations between India and Pakistan, these scenarios are neither realistic nor feasible at present. To begin with, Islamabad is unlikely to open GB’s borders or welcome Indian investment in the region. Also, it remains unclear which entity has actual control over the Wakhan Corridor, making the prospect of India’s investment there more of a dream than a reality. With the presence of Pakistan to the north, India is effectively cut off from Central Asia. While diplomatic ties and limited trade with Central Asian nations do exist, they remain minuscule in scale compared to the overall potential.

Conclusion

In 2020, the Imran Khan regime proposed elevating GB’s status to that of a province. China had been pushing for this, as it sought legal cover for its billion-dollar investments in CPEC. However, this proposal posed significant challenges for Islamabad. Additionally, legally absorbing GB into Pakistan would require Islamabad to shift away from its decades-old stance of supporting a plebiscite and, thus, compromising its broader Kashmir agenda and potentially being seen as a betrayal of the ‘Kashmiri Cause’. Consequently, whether or not to make GB Pakistan’s fifth province will not be an easy decision for Islamabad.20

While India would initially object to Pakistan’s formal integration of GB, the move could open up an opportunity to settle the Kashmir dispute with Pakistan. After all, India is in favour of freezing the status quo, allowing both countries to keep territory under their control by making the LoC the international border. Could CPEC then trigger a process to end the India-Pakistan dispute over Kashmir?21 As a former Indian foreign secretary recently observed, “Without Pakistani control over this disputed territory of GB, there would be no CPEC”. Hence, whatever steps Pakistan takes to strengthen its control over GB and importantly, to endow its relationship with the region with some legality, will be keenly watched in Beijing as well as Delhi.

Given all the benefits that open borders could offer to the region, a ‘Strategic De-escalation’ of regional tensions could pave the way for greater connectivity and increased economic benefits.22 Yet mitigating regional tensions will require high-level cooperation from all governments involved. A trilateral working group consisting of representatives from India, Pakistan and Afghanistan could be constituted to discuss the possibility of a road network linking Kashmir with Pamirs. The official opening of the LoC in 2005 and the establishment of J&K Joint Chambers of Commerce and Industry in 2011 were followed by increased economic activity and institutionalised trade ties.

The wishful opening of GB could produce similar opportunities, if it ever happens. Herein lies India’s opportunity to not only reunite GB with Kashmir and give the people their long-lost due sovereignty, but also leveraging its soft power. If that fails, we always have a powerful military, foreign office and intelligence agencies who can do the needful, minus the baggage of a conflict-ridden history. However, since this is more of wishful thinking than a likely happening, given the freeze in the Indo-Pak relations for over more than decade now. A more plausible course of action for India would be to place the issue on the back burner and concentrate on developing the part of Kashmir that it holds post the recently conducted elections and successful installation of a democratic state government there.

Endnotes

1 Hussain, S., “The History of Gilgit-Baltistan”, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, 26 Apr 2021, accessed on 21 Dec

2024,

https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277

2 “Map of Tibetan Empire citing areas of Gilgit-Baltistan as part of its Kingdom in 780–790 CE”, Rootshunt

3 Martin Sökefeld, “At the Margins of Pakistan: Political relationships between Gilgit-Baltistan & Azad Jammu and Kashmir”, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, accepted manuscript of an article published in: Ravi Kalia (ed.) 2015. Pakistan’s Political Labyrinths. New York, Routledge: 174. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315683195-9/margins-pakistan-martin-s%C3%B6kefeld

4 “India, Iran and Aryans”, Rootshunt,

https://rootshunt.com/aryans/indiairanandaryans/listofancientiranianpeople/gilgitbaltistan/htm

5 Pakistani president signs Gilgit–Baltistan autonomy order English Xinhua. News.xinhuanet.com. 2009-09-07.

6 Shafqat Hussain, “The History of Gilgit-Baltistan”, Oxford Research Encylopedias, 26 Apr 2021,

https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-378?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190277727.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190277727-e-378&p=emailAcuKOUGQA0ZqA

7 Ibid.

8 Discussion on Historum.com titled, “Was Gilgit and baltistan part of Afghanistan before Dogras annexed it”? Thread starter Aryan Khan Kushzai, 18 Dec 2017, https://historum.com...worldhistory...asianhistory

9 Dr. Hafeez Malik, “U.S. Relations with Afghanistan and Pakistan: The Imperial Dimension”, Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2008, pg-308.

10 “The Karakoram Highway”, Rootshunt

11 Minhas Majeed Khan et all., “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: A Game Changer”, The Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad, 2016, https://issi.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/CPEC_Book_2016.pdf

12 “China Pakistan Economic Corridor”, https://cpec.gov.pk/map-single/1

13 Sudha Ramachandran, “Unrest in Gilgit-Baltistan and the China-Pakistan economic corridor”, The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, 29 Sep 2016, https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13396-unrest-in-gilgit-baltistan-and-the-china-pakistan-economic-corridor.html

14 Vivek Kumar Mishra, “Sectarian Violence in Gilgit-Baltistan”, Jadavpur Journal of International Relations, 23(1), 1-25, https://doi.org/10.1177/0973598418789993

15 P. Stobdan, “The last colony: Muzaffarabad-Gilgit-Baltistan”, India Research Press with Centre for Strategic and Regional Studies, University of Jammu. ISBN 9788183860673, Apr 2008

16 “Mapping China’s Digital Silk Road”, Reconnecting Asia,19 Oct 2021, https://reconasia.csis.org

17 Surjeet Singh Tanwar, “Wakhan Corridor: India’s Possible Gateway to Central Asia”, Centre for Land Warfare Studies, 06 Sep 2021, https://www.claws.in/publication/wakhan-corridor-indias-possible-gateway-to-central-asia/

18 Pratek Joshi, “Gilgit-Baltistan”, Reconnecting Asia, 03 Mar 2017, https://reconasia.csis.org/gilgit-baltistan/

19 “Gilgit Baltistan: Caught Dangerously Between Regional Powers”, UNPO, 04 Mar 2011, https://unpo.org/gilgit-baltistan-caught-dangerously-between-regional-powers/

20 Sudha Ramachandran, The Complex Calculus Behind Gilgit-Baltistan’s Provincial Upgrade, The Diplomat, 14 Nov 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/11/the-complex-calculus-behind-gilgit-baltistans-provincial-upgrade/

21 Fahad Shah, Does the China-Pakistan economic corridor worry India?, Al-Jazeera, 23 Feb 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/2/23/does-the-china-pakistan-economic-corridor-worry-india

22 Pratek Joshi, Gilgit-Baltistan, Reconnecting Asia, 03 Mar 2017, https://reconasia.csis.org/gilgit-baltistan/

Colonel (Dr) Bhasker Gupta (Retd) is an Artillery Officer of Jun 1992 batch who superannuated from service in Dec 2022. Presently settled at Greater Noida, he engages himself gainfully in writing and teaching. He is a Professor of Practice at Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak for Defence and Strategic Studies. He is also a Senior Fellow and PhD guide at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, and a mentor and guide at the United Service Institution of India.

Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CLIV, No. 638, October-December 2024.

Author : Colonel (Dr) Bhasker Gupta (Retd),

Category : Journal

Pages : 673 | Price : ₹CLIV/638 | Year of Publication : October 2024-December 2024