Abstract

The 2020 Galwan Valley clash marked a critical juncture in India-China relations, highlighting China’s increasingly assertive tactics and emphasising the need for India to reassess its approach toward border security. This essay examines China’s strategic motives, including territorial expansion, historical claims, and geopolitical posturing, which have led to heightened tensions along the Line of Actual Control. By analysing the historical context, recent standoffs, and China’s broader aggression towards multiple nations, this essay reveals critical military lessons for India. Key recommendations focus on enhancing border infrastructure, fortifying intelligence and surveillance capabilities, and adapting to mountain warfare demands. Leveraging advanced technology, such as artificial intelligence and automated defence systems, can offer India a tactical advantage, while diplomatic initiatives, including military-to-military dialogues and confidence-building measures, remain essential for long-term stability. Military diplomacy, infrastructure upgrades, and diverse defence supply chains are proposed as strategic countermeasures to China’s aggression. The essay concludes that while diplomacy is paramount, India must simultaneously strengthen its military readiness to safeguard its strategic interests, ensuring it is better positioned for potential future confrontations along its northern borders. This comprehensive approach underscores India’s need for resilient strategies to counter China’s continued territorial assertiveness.

Introduction

In the past few years, China has shown its strong intentions regarding its disputes with major countries for its claims on superpower status through the aggressive use of economic and military gestures—with the United Kingdom on the issue of Hong Kong, with Australia on trade, with Japan over the ownership of the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, with the United States (US) on its projection of military power, and with Southeast Asian countries over control of the South China Sea, despite the verdict of the world court under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea agreement. The unprecedented display of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy in international forums, the aggressive stance over the Covid catastrophe, and the debt-trap policy are a few examples of how China is on the path to achieve Xi Jinping’s vision of a ‘Resilient China’. However, the recent attempts by China to stir up trouble on the India-China border, translating it into aggression in the Galwan River Valley, have severely added to the worries of not only India but also the international community. The Galwan Valley clash on 15 Jun 2020 between India and China marked one of the most serious military confrontations between the two Asian giants in decades. The skirmish resulted in casualties on both sides, shaking the diplomatic relations between the nations. This was a one-of-a-kind border clash, taking place between two nuclear power giants, which happened without a single shot being fired but resulted in one of the largest face-offs ever on the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The conflict remains unresolved, and both sides are maintaining a significant military presence along the disputed LAC. The mystery behind the true intentions of the ‘Dragon’ in abrogating border agreements remains unresolved, but it has unveiled that the Indian perception of its northern neighbour needs reassessment. Delhi requires a major rework in designing its strategy to match the ambitions of China.

This also necessitates that all efforts at political and military levels converge toward a common aim of disengagement and the establishment of the status quo on the LAC. At the same time, India should not lose sight of the overall game plan of Chinese geopolitics. Rather, it should manoeuvre to outlast Beijing’s attempts at disregarding India’s ambitions. However, it has been more than three years since the incident happened, and no permanent solution is in sight. This leaves no choice but to strengthen India’s stance in all spheres of the diplomatic, informational, military, and economic paradigm. Since the confrontation has its origin on the borders, the military sphere occupies a prime spot in dealing with the issue. Hence, this article sheds light on China’s aggression in the Galwan Valley and the military lessons India can draw from this confrontation to curb Chinese progress on the LAC.

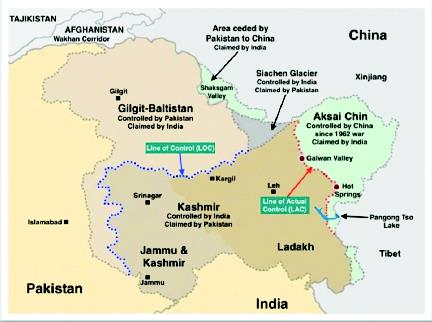

Map 1: Map showing Line of Control (LoC) and LAC1

Historical Context and Agreements on Confidence Building

The Sino-Indian border, which lies mostly in the Himalayan region, has always been a contentious issue. Despite repetitive rounds of negotiations between the two, there has been no success achieved so far to demarcate the LAC conclusively.2 After India gained independence in 1947 and the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, the status of their border became an issue, primarily in two regions of Aksai Chin and Arunachal. Aksai Chin is in the western sector where China built a road connecting Xinjiang to Tibet through this region, which India claims as part of its Ladakh territory. Arunachal Pradesh is in the eastern sector, where China never recognised the McMahon Line and claimed a significant part of what is today’s Arunachal Pradesh. In 1962, territorial disputes and skirmishes escalated into a full-fledged war between India and China. The war ended with China declaring a unilateral ceasefire, but the boundary issue remained unresolved. China retained control of Aksai Chin, which it had occupied, while India continued to maintain control of Arunachal Pradesh. Subsequently, several rounds of border talks began in the 1980s, aiming to bring about a negotiated settlement acceptable to both nations. Consequent to which, several border agreements have been concluded between the two nations which are as under3:

- 1993 Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas. It recognised the LAC as the effective border between the two countries and set out the basic principles to prevent border disputes from escalating. Both sides agreed to reduce or limit their military forces in areas where they are in proximity.

- 1996 Agreement on Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas. This agreement expanded upon the 1993 agreement by laying down explicit provisions for the reduction of military forces and maintaining peace along the LAC. Specific restrictions were put on air force flights, and large-scale military exercises close to the LAC.

- 2005 Protocol on Modalities for the Implementation of the Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field Along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas. This protocol was a follow-up to the 1996 agreement and provided detailed modalities for the implementation of the confidence-building measures that were previously agreed upon.

- 2012 Agreement on the Establishment of a Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs. This agreement established a mechanism to ensure that border affairs are effectively managed, consultations are held regularly, and any differences or disputes are addressed in a timely manner.

- 2013 Border Defence Cooperation Agreement. This was signed to ensure that patrolling along the LAC does not escalate into conflicts. It includes measures such as both sides not following or tailing patrols of the other, not using military capability to harm the other, and setting up a hotline between military headquarters.

However, over the years, despite multiple rounds of negotiations and talks, the exact demarcation of the LAC has remained a contentious issue. Both sides periodically accuse each other of patrolling and building infrastructure across their perceived lines. Notably, there was a significant escalation in 2020 in the Galwan Valley.

The Galwan Standoff

The Galwan Valley lies at the heart of this disputed territory and holds strategic importance for both countries. Galwan, due to its proximity to the vital road link of the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie Road, is of particular importance. This road, passing near the Galwan Valley, improves India’s access to the northernmost part of its territory, providing logistical advantages to India. Also, the Galwan Valley’s proximity to Aksai Chin provides a strategic upper edge to India in the larger India-China border dispute context. Since China has significantly improved its infrastructure in the Tibetan plateau, which allows it to quickly mobilise its forces, maintaining and enhancing India’s infrastructure, including in areas like the Galwan Valley, acts as a counterweight against the infrastructural advantage enjoyed by China in the region.

The tensions in the Galwan region started escalating in early May 2020. Chinese troops reportedly began setting up tents and infrastructure in an area that India claims as its own. By mid-Jun, the friction led to violent hand-to-hand combat.4 While firearms were not used due to a 1996 agreement prohibiting the use of guns and explosives at the LAC, the skirmish led to the death of 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese casualties. It is imperative to mention here that the Galwan Valley clash in 2020 is tragic and a definite inflection point in Sino-Indian ties, but it certainly did not come as a surprise.

Reasons Behind China’s Aggression

Principle of Historic Rights and Dwindling Claim of Sovereignty. China has often invoked the principle of ‘Historic Rights’ to assert its claim over Indian territories5, e.g., the claim to the South China Sea. On 19 Jun 2020, just four days after the deadly clashes, Zhang Yongpan, a scholar with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, referred to instances of territorial control by the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) and western literature as justification for China’s claim over the Galwan Valley. This claim was soon followed by a statement from the Chinese Foreign Ministry asserting its sovereignty over the valley.6 Making claims solely based on the ‘Principle of historic rights’ is entirely ambiguous, baseless, and has no grounds in well-defined nation-state practices. However, China has been progressing its stakes without adhering to any international laws and judgments, resulting in disputes between China and several of its neighbours. The same tactics have been applied by China with India in Ladakh as well as Arunachal Pradesh, even though sources and references from history books do not always translate into exact cartographic outputs and may not necessarily be true.

Prodding and Provoking Tactics. According to Parliament records, between 2016 and 2018, over 1,000 incidents of transgressions by Chinese troops were noted.7 China’s strategy to keep the issue of the LAC simmering and provoke seemingly arbitrary transgressions or face-offs is part of a well-coordinated arrangement under the top hierarchy of the Communist Party of China (CCP), with the likely aim of seizing territory and distorting the alignment of the LAC.

Strategic Deceit. The Chinese top hierarchy has often displayed a ‘Mindful but duplicitous’ mindset in their thinking toward India. China has always been cautious about the modernisation of the Indian Armed Forces and strives to deter any Indian advantage, yet it simultaneously disregards India’s military capability, citing a lack of inventory, poor quality, and time lags as reasons. In Oct 2019, ahead of the summit between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi, China objected to India conducting ‘Op Him Vijay’, one of its biggest war games in Arunachal Pradesh. Despite clarifications that the exercise is an annual feature, the Chinese pushed to postpone the meeting. Similarly, in 2014, while President Xi was being hosted by PM Modi in his home state of Gujarat, the People’s Liberation Army carried out incursions along the borders.8 Arguably, as the Doklam incident has proved, China’s forays into South Asia, including adventurism in the Indian Ocean region or on the disputed borders, are often aimed at imposing reputational costs on India. Beijing frequently views the Sino-Indian relationship through the lens of Sino-US and Indo-US relations, reflecting Chinese anxiety. In the words of the late Cheng Ruisheng, a veteran diplomat and former Chinese ambassador to India who championed a stable Sino-Indian relationship, “We don’t feel stress with regard to India, in part because China is militarily stronger”. Cheng added, “I think, frankly speaking, we are somewhat concerned about the cooperation between India and the US, especially in the sphere of security”. Speaking nearly a decade ago, he stressed, “The China-US relationship, the China-India relationship, and the India-US relationship are inclusive of each other. Balance is very important”.9

China’s Ideology of Increased Assertiveness Against India. Although China’s stance post-Galwan carries divergent meanings on the domestic and international fronts for India, China’s actions on the LAC signal serious intent, and any attempt to hinder China will likely be perceived as a threat to its expansionist ambitions. Several concealed agendas exist behind China’s increased assertiveness against India on the LAC:

- Strategic Depth. China might aim to push the LAC further west, providing its National Highway 219, linking Tibet and Xinjiang, with more security.

- Geopolitical Messaging. By taking an aggressive stance, China might be signalling to India (and other adversaries) its willingness to escalate territorial disputes.

- Internal Politics. Domestic factors in China also play a role. Showing strength against foreign adversaries, real or perceived, can bolster the image of the CCP within the country and consolidate its hold on power.

- Diversion. Amid internal challenges, such as the Hong Kong protests and international scrutiny over its handling of the Covid outbreak, the border clash could divert domestic and international attention.

- Economic Corridor. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative. It provides China with a direct route to the Arabian Sea, bypassing the Strait of Malacca, which can be a chokepoint in case of naval blockades. This ensures a continuous flow of energy and trade, even if maritime routes face disruptions.

- Access to Pakistani Military Bases. While not openly admitted, with a secure CPEC, it is speculated that China could gain access to military and naval bases in Pakistan, which would extend its power projection capabilities.

Military Lessons for India

With a history that ranges from the 1962 Sino-Indian War to recent skirmishes along the LAC, India has had several opportunities to introspect and draw valuable military lessons in its approach toward China. This analysis aims to shed light on these lessons, emphasising the evolving nature of warfare, the importance of technological and logistical advancements, and the need for diplomatic acumen to accompany military strategies. As both nations continue to assert their roles in a multipolar world, the understanding and implementation of these lessons become pivotal for India to ensure regional stability, national security, and the safeguarding of its strategic interests. The following lessons are pertinent:

- Enhanced Border Infrastructure. Investing in infrastructure along the border regions would allow for quicker troop movements and better logistical support.

- Improved Intelligence and Surveillance. Enhancing capabilities for real-time intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance would be vital to keep Chinese developments under continuous observation. Any deviation from mutually agreed regulations shall be met with an appropriate response at bilateral as well as international levels.

- Mountain Warfare Training. Given the terrain of the India-China border, specialised mountain warfare training should be a priority for all personnel of the armed forces as well as paramilitary forces deployed on the LAC.

- Rapid Deployment Options. The ability to quickly mobilise and deploy forces to contested regions can act as a deterrent and provide strategic flexibility. Akin to Chinese Trans-Regional Support Operations, India’s forces need to develop capabilities in strategic mobility.

- Diplomacy and Military Coordination. The importance of close coordination between diplomatic and military strategies cannot be overlooked. Both fronts should be synchronised to avoid mixed signals. Unlike what happened during President Xi’s visit to India in 2014, when the Chinese army carried out multiple transgressions on the LAC, Indian military and diplomatic strategies should be in tune with each other.

- Diverse Supply Chains. Reducing dependency on a single country for military hardware and technologies would ensure that the armed forces are not compromised in the event of a conflict. In the event of conflict with China, which is nearly self-sufficient in war inventory and capable of influencing military hardware suppliers, India needs diverse supply chains to fulfil its defence requirements.

- Theaterisation/Enhanced Joint Operations. Promote better coordination between the Indian Army, Air Force, and Navy for joint operations, ensuring a combined and holistic approach to warfare. Theaterisation is much needed to counter the strategy of Chinese Theatre Commands.

- Robust Electronic Warfare (EW) and Cybersecurity Capabilities. With the growing threat from Chinese cyber warfare, ensuring the security of communication systems, equipment, and data is paramount. EW/Cyber Battalions must become integral parts of formations.

- Understanding Asymmetric Warfare. Recognising that not all confrontations will be direct and understanding the nuances of grey-zone warfare, cyberattacks, and propaganda wars is crucial. Collusion with Pakistan, water wars, cartographic aggression, and influencing neighbours are some of the examples where India needs to tackle China on favourable terms. The Indian Army must factor these elements into its military strategy.

- Modernising Equipment. Continually updating and modernising equipment ensures that the forces are prepared to face modern threats.

- Technological Leverage/Incorporating Technology

- Technology has become an indispensable part of modern military strategy. How Indian forces can leverage technology to bolster their position against China along their borders is given below:

- Surveillance Drones. Deploy drones to monitor border areas continuously. These can provide real-time updates, track enemy movement, and be used for reconnaissance missions without risking human lives. Drones should become part of the inventory at the sub-unit/detachment level.

- Satellite Surveillance. Invest in advanced satellite capabilities to monitor large stretches of land, especially in hard-to-reach terrains. This provides a bird’s-eye view of troop build-ups, infrastructure developments, and other activities.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI). Employ AI for predictive analysis. Machine learning can analyse patterns in enemy movements, predict potential hotspots, and offer strategic recommendations.

- Modern Communication Systems. In a conflict scenario against China, owing to its EW capabilities, the security of information and forces can only be ensured by modern encrypted communication systems. These systems can establish secure communication between troops and command centres, minimising the risk of interception and eavesdropping by the enemy.

- Sensor Networks. Deploy advanced sensor networks along the border that can detect vibrations, sound, and other metrics. These sensors can alert forces about any significant movement or activities on the other side.

- Automated Defence Systems. India needs to invest in modern automated defence mechanisms, such as missile defence systems or automated gun turrets that can respond to threats in real-time and cater to surprise or unanticipated threats.

- Advanced Weaponry. Equipping forces with advanced weaponry integrated with technology is the need of the hour. Smart guns, guided missiles, and laser-based systems can provide a significant edge in conflict scenarios.

- Virtual Reality (VR) Training. Use VR to simulate border scenarios and train troops. This can prepare them for various eventualities, from hand-to-hand combat in rugged terrains to coordinating technological assets during a skirmish.

Military Diplomacy

Military diplomacy is an essential tool in the broader diplomatic arsenal of any nation, aiming to build trust, foster understanding, and mitigate conflicts. For India, which shares a complicated relationship with China, military diplomacy can take several forms:

- Military-to-Military Dialogues. Establish regular high-level dialogues between the military leaderships of both countries. This can address mutual concerns, reduce misunderstandings, and pave the way for confidence-building measures.

- Joint Military Exercises. Organising joint military exercises can enhance trust and understanding between the armed forces of both countries. These exercises can focus on fields like counterterrorism, anti-piracy, or humanitarian assistance. Although the scenario has bleak possibilities, it can be exploited to enhance mutual trust.

- Defence Attachés. Increase the presence and role of defence attachés in respective embassies. They play a vital role in building bridges between the military establishments of both countries.

- Observation of Military Exercises. Allow military officers from one country to observe the other’s military exercises. This provides transparency and reduces suspicions about military intentions.

- Exchange Programs. Promote exchanges of junior and senior military officers for training and education. Experiencing the military culture of the other country first-hand can foster better understanding and rapport.

- Establish Hotlines. Set up more direct communication lines between top military officials on both sides. This can help quickly resolve misunderstandings and prevent minor issues from escalating.

- Mutual Agreements on Border Management. Establish clear protocols and agreements on managing border issues, patrols, and engagements to prevent incidents like the Galwan Valley clash in 2020.

- Multilateral Platforms. Engage constructively in regional and global military forums and platforms, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus. These platforms can be utilised for constructive dialogues and building regional trust.

Conclusion

The Galwan Valley clash in 2020 illuminated the intricate complexities of the India-China border dispute and was a grim reminder of the simmering tensions that exist between India and China. It also emphasised the paramount importance of strategic preparedness for India. At the strategic level, it underscored the value of rapid infrastructure development, the necessity of diversifying defence supply chains, and the crucial role of robust diplomatic engagements. At the armed forces level, the incident highlighted the need for joint military training, building military alliances, and leveraging advanced technology in modern warfare. For the Indian Army, Galwan stands as a stark reminder of the challenges it faces and the lessons it must internalise to ensure no such opportunity is ever again thrown in front of the Chinese for their exploitation.

While diplomatic channels must always remain the primary tool for conflict resolution, India’s armed forces can take several military lessons from the episode. Strengthening its defences, re-evaluating outdated agreements, and developing infrastructure near the border are imperative steps toward ensuring that India is better prepared for any future confrontations.

Endnotes

1 Map taken from upscwithnikhil.com

2 M. Taylor Fravel, “Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China’s Territorial Disputes”, Princeton University Press, accessed 23 Aug 2023,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7s2s6

3 Nayanima Basu, “Why India needs new confidence building measures to clarify LAC issue with China”, The Print, 13 Sep 2020, accessed 23 Aug 2023,

https://theprint.in/diplomacy/why-india-needs-new-confidence-building-measures-to-clarify-lac-issue-with-china/502995/

4 Rajagopalan, Rajeswari Pillai, “China-India Relations: 2 Years After Galwan Clash”, The Diplomat, 17 Jun 2022,

https://thediplomat.com/2022/06/china-india-relations-2-years-after-galwan-clash/

5 Utkarsh Pandey, “The India-China Border Question: An Analysis of International Law and State Practices”, Observer Research Foundation, 16 Dec 2020, accessed 01 Sep 2023,

https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-india-china-border-question/

6 “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, 19 Jun 2020.

7 Shruti Pandalai, “Lessons for India After the Galwan Valley Clash”, The Diplomat, 31 Jul 2020, accessed 27 Aug 2023,

https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/lessons-for-india-after-the-galwan-valley-clash/

8 Jason Burke & Tania Branigan, “India-China border standoff highlights tensions before Xi visit”, The Guardian, 16 Sep 2014, accessed 27 Aug 2023,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/16/india-china-border-standoff-xi-visit

9 Pandalai, “Lessons for India”

Lieutenant Colonel Yogeshwer Rana was commissioned into the Army Air Defence of the Indian Army. He is currently posted at the Army Air Defence College. This is the reproduction of the winning entry from the Lietenant General SL Menzes Memorial Essay Competition.

Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CLIV, No. 638, October-December 2024.

Author : Lieutenant Colonel Yogeshwer Rana

Category : Journal

Pages : 698 | Price : ₹CLIV/638 | Year of Publication : October 2024-December 2024