Abstract

This essay explores the rehabilitation and career prospects of war-wounded soldiers, focusing on current systems and areas for improvement. While the armed forces provide initial medical treatment, long-term rehabilitation procedures often lack standardisation and comprehensive support, leaving personnel dependent on personal resilience and family support. Through qualitative and quantitative methods, this study gathers perspectives from affected soldiers, highlighting deficiencies in psychological care, inadequate facilities, and bureaucratic challenges, such as the L1 procurement process that delays access to quality medical implants and prosthetics. The need for standardised rehabilitation protocols, partnerships with non-governmental organisations, and advanced civilian medical centres is emphasised. Key recommendations include implementing a structured, multidisciplinary approach to care, improving mental health support, and fostering a sense of purpose within the organisation to motivate recovery. The inclusion of veteran-led civil organisations like Conquer Land Air Water, which empowers war-wounded soldiers by demonstrating their continued value and resilience, underscores the potential for reintegration into society and the workforce. This analysis advocates for systematic reforms to ensure war-wounded soldiers receive the support necessary for meaningful rehabilitation and re-engagement, benefiting both the individual and the broader military community.

Introduction

“The soldier, above all other people, prays for peace, for he must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war”1

The profession of arms has always been one that requires the highest levels of commitment, resolve, and, above all, sacrifice. This sacrifice, however, does not come easy for everyone, and some of our bravest come back from war with scars that may last a lifetime. It is imperative to understand that while the nature of war remains constant, the character of warfare is ever-changing. The lethality and range of weapons have made warfighting an attrition-based affair, wherein, loss of life is not only imminent but guaranteed. During these conflicts, numerous lives have been lost; however, more have been wounded and are now forced to live half a life with struggles and trauma that most cannot even fathom.

There are nearly 40,000 war-wounded personnel in our country, and this number is constantly increasing. With the extent of injury deciding the fate of the soldier, some may become permanently disabled and are invalided out of service, while the remaining continue to serve with disabilities. The commemorative medals and financial grants, although important, cannot be compared to the emotional support required. The importance of care and constantly catering to the requirements of our war-wounded would go a long way in ensuring that none of the serving soldiers think twice before proceeding on an assigned mission, no matter how dangerous.

Terminology

Rehabilitation.2 Rehabilitation is a process of assessment, treatment, and management by which individuals (and their families) are supported to achieve their maximum potential for physical, cognitive, social, and psychological functions, participation in society, and quality of living.

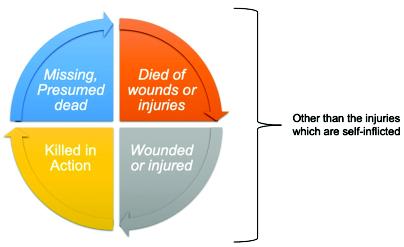

Battle Casualty.3. Battle casualties are those which are sustained in action against enemy forces or in preparation for/deployment to operations on land, sea, or air. Casualties of this type consist of the categories as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Battle Casualties – Types

Amputation.4 Amputation is an acquired condition that results in the loss of a limb, usually from injury, disease, or surgery. Losing a limb due to accidental trauma or disease has an enormous impact on a person’s body, emotions, relationships, vocation, and way of life.

Understanding the Process of Rehabilitation for the War-Wounded

The methodology adopted to understand the issues with the current rehabilitation procedures in our armed forces must consist of both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The qualitative method involves interactions in the form of interviews, while the questionnaire forms part of the quantitative method.

Qualitative Method. Through personal interactions, three soldiers were interviewed in a detailed one-on-one setting, which provided insight into their individual struggles. These views, highlighted in the following paragraphs, are unique to everyone. While the level of satisfaction varies, it was clear that support from the service or branch played a significant role in their recovery.

The Ace Fighter Pilot. The officer, a SU-30 pilot, gave a first-hand account of his ejection and how he lost his leg in the process. This story is particularly significant, as most pilots involved in crashes are not alive to recount their ordeals in detail. Key points that emerged during the discussion are as follows:

- Even after multiple conflicts and casualties in the armed forces, there is still no standardised methodology for rehabilitation; it remains largely dependent on the individual’s personal resilience.

- Psychological rehabilitation requires improvement, as merely sending doctors to assess mental stability may be insufficient.

- While the injury centres are equipped with new rehabilitation facilities, basic amenities like ramps and wheelchair-accessible pathways are lacking.

- The Artificial Limb Centre (ALC) in Pune played a crucial role in helping the officer set a clear goal toward gaining independence post-rehabilitation.

- Physiotherapists are like drill instructors at the academy, focused solely on achieving progress at a set pace, which may not be suitable for patients of all mental capacities.

- In this case, the service played a key role in the officer’s recovery, providing transportation support and allowing his wife (also a serving Air Force officer) to be attached to various locations on temporary duty to assist him. This support has reinforced his commitment to the service.

- The officer considers himself fortunate and has come to terms with his disability, which has not deterred him in any way.

- The service and the Commandant, ALC were instrumental in providing him with a better rehabilitation and guiding him in a way which was suitable and helped him to remain focussed.

Image 1: The Fighter Pilot with his Ottobock Prosthetic

The Land Mine Survivor. The Army officer interviewed was posted in Naushera District at the Line of Control at the time of his injury. Encountering a mine during an operation, he was airlifted to Command Hospital, Udhampur, where he underwent one of the best reconstructive surgeries, which saved the remaining part of his left leg. Some relevant extracts from his responses are as follows:

- A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for rehabilitation procedures was also absent in this case, making the process entirely human-centric and dependent on the patient’s capability.

- The staff at the ALC, though supportive, was severely limited due to the large number of patients needing attention.

- The prosthetic provided to the officer was not correctly constructed, leading to discomfort. He approached the ALC for reconstruction; however, the issue remained unresolved.

- The officer was mentally resilient during rehabilitation and did not require psychological support; however, he noted that the psychologists initially assigned to him were there merely for formality.

- The officer approached the ALC for his second prosthetic but was unable to make progress and ultimately had to finance his own limb from Ottobock Pvt Ltd.

- The non-availability of the required prosthetic was attributed to the ‘Make in India’ certification required for procurement on an L1 basis.

- The officer is still awaiting his second, improved prosthetic and is now in the process of purchasing another personally financed limb.

Image 2: Amputated Left Foot Image 3: Personally financed Prosthetic

The Marine Commando Who Beat Death. The officer’s story has surfaced on multiple occasions, but his internal struggles are known to few. Injured during Counter Insurgency Operations in Jammu and Kashmir, he arrived at hospital clinging to life after a grenade blast, with splinters throughout his body. Despite multiple internal injuries, he overcame the odds with the unwavering support of his family. However, the struggle for full health continues after being diagnosed with cancer and other lung ailments. The excerpts from his interview are as follows:

- Rehabilitation procedures assume that, as a soldier, the patient is mentally prepared to endure the ordeal and does not require emotional support.

- Civilian rehabilitation differs in that a visit to the doctor can be solely for communication. This is not so in the armed forces, likely due to the organisational structure.

- Physical support, though present, cannot substitute for the psychological support needed.

- Physical injuries are visible and often elicit sympathy or empathy, whereas, internal injuries are frequently overlooked and must be reiterated by a patient.

- It is essential to recognise that while a patient might prioritise physical rehabilitation, a sense of purpose and the will to continue in the same line of work can only be provided by the organisation.

- High-quality medical equipment, such as stents and pacemakers, is still procured via the L1 route, resulting in lower-quality materials and delayed timelines.

- During his time in the Intensive Care Unit, the officer looked forward each morning to interact with the doctor or nurse, underscoring the importance of physical compassion.

- There are ongoing challenges in providing manpower to tend to the patient initially.

- The ability to provide for the wounded sends the strongest message; not only to other disabled soldiers, but also to the entire serving community.

The questions that come to mind after interacting with these officers are straightforward and centre around the following arguments:

- What is the driving force behind war-wounded soldiers, and how does it inspire them to perform their duties, sometimes even better than others?

- Why are there no SOPs in place for psychological rehabilitation, and why is it regarded as merely a formality?

- Why is the L1 procurement procedure being followed for medical implants and prosthetics, resulting in the purchase of low-quality materials and delayed timelines?

- Are there any Memorandum Of Understanding (MOUs) in place with Non-Governmental Organisation (NGOs) and other civil hospitals/treatment centres for financing and providing medical aid, including rehabilitation, for war-wounded soldiers?

- Why are basic amenities that assist disabled soldiers in their daily routines, such as ramps, parking spaces, and accessible washrooms, not available at various institutions where personnel may be posted?

Quantitative Method. As part of the quantitative analysis, a research questionnaire was circulated exclusively among war-wounded personnel, both serving and retired. The research focused on exploring the following areas:

- To gauge the levels of satisfaction personnel had regarding the rehabilitation process.

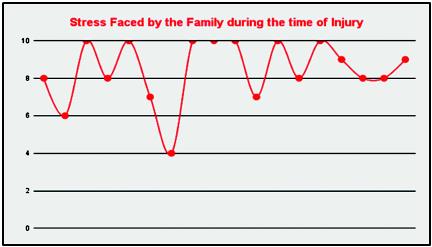

- To assess the levels of stress experienced during the time of injury, particularly by the patients and their families throughout rehabilitation.

- To gather views on the general attitude of the service towards war-wounded personnel, whether it is sympathetic, empathetic, or disdainful.

- To seek recommendations on facilities that could be provided to families who care for patients during rehabilitation.

- To examine the desire to continue serving in the armed forces despite a disability.

Data Analysis of Questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed exclusively within the war-wounded community, excluding regular service personnel, to ensure the feedback’s accuracy and to avoid merely populating responses. Although the number of responses was limited, the soldiers who participated offered key recommendations, as detailed below:

- Only 38 per cent of respondents were satisfied with the rehabilitation provided by the services, with satisfactory rehabilitation primarily for gunshot wounds.

- 30 per cent of respondents were dissatisfied with rehabilitation procedures, and 66 per cent opted to seek privately financed rehabilitation sessions at civilian medical centres.

- All respondents (100 per cent) felt that psychological rehabilitation was necessary but had been lacking in their treatments. Additionally, 72 per cent reported experiencing high levels of post-traumatic stress, which they overcame largely due to the support of their loved ones.

- 72 per cent felt that the environment remains sympathetic toward the war-wounded, with considerable room for increased empathy.

Organisational Issues and Constraints

To fully understand the issues, they may be categorised under three sub-headings: Care, Career Prospects, and Rehabilitation. These are detailed in the succeeding paragraphs.

Care and Rehabilitation.

- Resilience and Complete Care. Building and maintaining resilience among military and veteran communities is essential for promoting successful reintegration into civilian life. The importance of a comprehensive care package—including pre-operative and post-operative care with therapy—is notably absent from the current rehabilitation process. This may stem from doctors and caregivers perceiving military patients as inherently resilient due to their training and service, thus, overlooking the need for support. Consequently, many patients rely solely on their loved ones, who may not always be able to provide adequate support, potentially prolonging the rehabilitation period and leaving patients struggling internally even after physical recovery.

- Absence of Standard Operating Procedures for Psychological Rehabilitation. Current procedures are personality-based; for example, two war-wounded personnel were personally counselled by the Commandant of ALC, Pune, which led to quicker recoveries. However, this was due to the personal interest of the officer-in-charge of their rehabilitation. This personalised attention is not guaranteed for every patient, leaving those with weaker personal resolve or less mental stability facing extended recovery timelines.

- Overtasked Medical Facilities. Due to the large number of patients visiting medical facilities, most doctors are occupied with routine tasks, leaving little time to focus on the rehabilitation of critical patients. Consequently, patients often struggle to ask questions or have their queries addressed. Although physiotherapists at the ALC are successful in helping patients achieve physical rehabilitation goals, they frequently proceed without considering the patient’s mental adaptability.

- L1: Method of Procurement. Mixed feedback has been received on the quality and timely provision of prosthetics. While one patient received a prosthetic worth 37 lakhs, another was forced to personally finance a foot plate from the leading prosthetic manufacturer, Ottobock, due to the absence of a ‘Make in India’ certification. This procurement method has led to delays in acquiring crucial items, such as heart stents and pacemakers, which paints a troubling picture of the current system.

- Service-Specific Care. The level of care provided by each service can significantly impact recovery times. Although the air force played a key role in supporting the above-mentioned fighter pilot with necessary airlifts and assistance, the army, due to its higher number of patients, was unable to offer a similar level of individualised support.

- Facilities at Leading Civil Hospitals vs Military Medical Centres. A holistic comparison between the facilities at leading hospitals and military rehabilitation centres reveals significant gaps, particularly in family accommodations, basic amenities, and available rehabilitation equipment. These gaps underscore the insufficient funding allocated within the defence budget for comprehensive rehabilitation resources.

Career Prospects.

- Desire to Serve. Over 95 per cent personnel who responded to the questionnaire expressed a desire to continue serving, even though stress levels and rehabilitation procedures need significant improvement. The will to serve remains strong; however, many soldiers feel left out upon returning to their parent organisations. Initial sympathy often turns to empathy, which may eventually give way to disdain.

- Employability in Suitable Jobs. Not all soldiers are required on the front lines; some may be needed in roles that ease the burden on their counterparts who have gone through similar ordeals. The affiliation of the Services Sports Control Board with the Paralympic Committee of India, for example, is a positive step; though it requires focused attention, with the navy and air force encouraged to follow suit. Personnel transfers are conducted via COPE coding, yet it can be a continuous struggle for disabled soldiers to prove their capabilities within the organisation, often leaving them frustrated.

- War-Wounded and Battle Casualty Classification. Feedback suggests that many soldiers struggle to validate their casualty status within the current system. While some individuals may have taken advantage of the system to secure disability pensions, genuine patients face daily challenges in obtaining enhanced emoluments.

- Transition to the Outside World. The rules governing wounded personnel’s transition to civilian life are outdated, offering minimal ex-gratia and limited medical coverage. These issues are even more pronounced for cadets who are discharged from academies due to injury. Additionally, entitlements vary significantly by state, adding further inconsistency.

Way Ahead and Recommendations

Systematic Care and Rehabilitation.

- Composite Care Package. The war-wounded personnel who participated in the survey were fully satisfied with the first aid and surgeries provided by doctors. However, corrective surgery is merely the beginning of the rehabilitation process. Drawing from the United States’ ‘Promoting Successful Integration’5 program for veterans and war-wounded personnel, a comprehensive care package should include a multidisciplinary rehabilitation team as given in Figure 2.

Figure 2

- Step-by-Step Analysis. A systematic analysis by each expert on the team would help determine the patient’s strengths and weaknesses, thereby, emphasising the recovery process. Even if the existing system lacks the necessary expertise, MoUs with civil agencies and financial aid from NGOs would support the service in achieving the desired outcomes. It is essential that therapists and engineers assess patients early in the rehabilitation process to identify any psychological barriers that may hinder recovery. Social support and a sense of purpose can be crucial for a wounded soldier striving to reintegrate as an active member of the forces.

- Mental and Physical Pain Management. Pain management was a significant concern raised by respondents, specifically regarding the side effects of heavy medication, which should be clearly communicated to the patient upfront. A briefing on injuries in the presence of a psychologist is likely to promote a positive outlook on recovery.

- Formulation of Standard Operating Procedures. Many institutions worldwide, such as the Borden Institute6 and Headley Court7, have established rehabilitation procedures that outline processes for various injuries. These documents could serve as references to develop an SOP, with input from medical experts from both military and civilian sectors. Detailed Project Reports could be approved for these projects, in collaboration with leading hospitals, to establish a National Defence Rehabilitation Centre, thus, fostering a more motivated and battle-ready workforce.

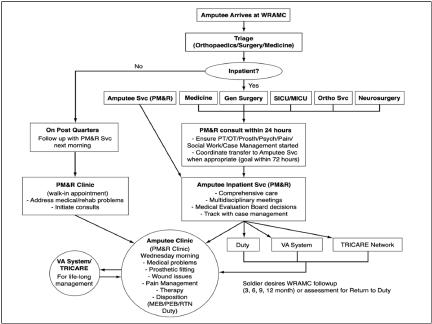

- Amputee Care Program.8 The number of amputees in the country is relatively small, warranting dedicated attention from all three services. Providing advanced prosthetics would represent a minimal fraction of the defence budget but would ensure that service members can perform their duties confidently and without hesitation. The L1 procurement system for prosthetics should be eliminated, as it not only extends timelines but also results in the purchase of low-quality materials that require frequent replacements, thereby, incurring higher cumulative costs. Establishing MoUs with companies like Ottobock would be a step in the right direction to ensure complete satisfaction for disabled soldiers and to encourage them to engage in sports, providing a meaningful reason for continued existence. A schematic flowchart of amputee care is shown in Appendix ‘C’.

Career Prospects.

- Raison d’être. Analysis of the questionnaire responses revealed that all respondents desired to continue in service despite facing numerous challenges in transitioning back to their core roles. However, a sense of purpose—something that can only be provided by the organisation—plays a crucial role in their recovery. The simplest approach for any organisation might be to sideline the affected soldier, leaving them isolated and potentially questioning their abilities. Instead, continuous engagement and a sense of belonging can pave the way for sustained productivity.

- Career Prospects within the Services. Interactions indicated that most soldiers have come to terms with the limited prospects of rising in the hierarchy due to their injuries. However, denying them the opportunity to serve in a similar capacity as their original role could signal a lack of faith. The example of Captain Christy Wise of the United States Air Force, who returned to active flying after losing her right leg, illustrates how such soldiers can excel. While limitations may exist, assigning these individuals to suitable roles at Headquarters, where their expertise and years of service are invaluable, allows them to continue contributing meaningfully.

- Specialist Civil Organisations. With increased media interconnectivity, organisations like Conquer Land Air Water (CLAW) have brought widespread attention to the achievements of war-wounded soldiers. Founded by veterans Major Vivek Jacob and Major Arun Ambathy, this organisation has gained prominence by taking disabled soldiers to the highest battlefield, Siachen, and is now set to break the world record for the largest SCUBA Occupational Therapy and Skill Training program for people with disabilities. Such organisations challenge outdated perceptions of limited capabilities, with disabled personnel leading these initiatives. Many war-wounded veterans have now joined CLAW, gaining opportunities to teach, learn, and work toward independence. The organisation strives to eliminate pity, glorify soldiers’ injuries, and foster a sense of invincibility.

Conclusion

While there is currently a system in place within the services to monitor and support war-wounded personnel in the country, the rehabilitation procedures remain personality-centric and require a dedicated effort. This includes the formulation of SOPs, partnerships with NGOs and civilian medical organisations to establish state-of-the-art facilities, and improvements in the procurement of prosthetics. The removal of the L1 procurement procedure for medical implants, which are critical for the survivability of war-wounded personnel, is essential to ensure they have a better chance of maintaining health and are motivated to make a swift transition back into service or civilian life.

@Commander Anirudh K Singh was commissioned into the Indian Navy in 2011 and is an alumnus of Rashtriya Indian Military College-Dehradun, National Defence Academy, Pune, and Defence Services Staff College. A Marine Commando Officer, he has served in Marine Commando Force operational units in Mumbai and Visakhapatnam, specializing in airborne operations, procurement, and SOP formulation. He has also been the Diving Officer on INS Vikramaditya and Executive Officer on INS Kirch. Currently, he is Commander (Special Operations and Diving) at Naval Headquarters, New Delhi. This is the reproduction of the winning entry from the War-Wounded Foundation Joint Essay Competition.

Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CLIV, No. 638, October-December 2024.

Appendix ‘A’

Details Of Questionnaire

Ser Details of Question Response

No Required

1. Army

Navy

Air Force

Paramilitary

2. Serving

Retired

3. Individual

4. Individual

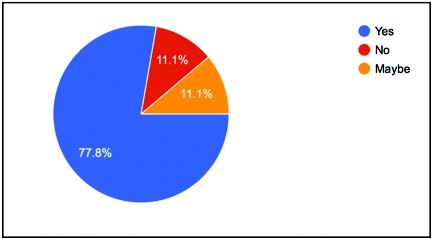

5. Yes

No

6. Yes

No

7. Individual

8. Married

Single

9. Yes

No

10. Individual

11.

Service

Whether Serving or Retired

Years of Service (In Years and Months)

Unit/Formation

Have you been in Active Combat situations/Conditions of High Stress as a Team Member or Team Leader?

Were you injured during the Active Combat Situation/Conditions of High Stress?

Date of injury?

Were you Married or Single during the time of injury?

Did you have children during the time of injury?

If you had children what were their ages during the time of your injury?

During the time of your injury and subsequent rehabilitation did you ever feel that your family went through extremely stressful situations. This may be rated on a linear scale.

Linear Scale from 1 to 10 ‘1’ being the least amount of stress ‘10’ being the least amount of stress

(The stress borne by the family generally goes unnoticed during the time of injury and during the rehabilitation process. This question would help us understand whether this led to additional stress for you and the family)

12. Type of Injury and Restrictions Imposed if any (The question is aimed at analysing the type of injuries being suffered and drawing inferences from the area of operations. I would request descriptive answers, so that I am able to analyse and recommend the kind of rehabilitation which should be focussed on)

13. Whether Amputee

14. If Amputee, then were Prosthetics Limbs provisioned by: Enterprises

15. For Amputees, If Prosthetics were provided, then are they meeting your requirements or need further improvement

16. Time Accorded for Rehabilitation (Please mention if still ongoing)

17. Number of Sessions undertaken for Rehabilitation (Please mention if still ongoing)

Individual

- Yes

- No

- Service Rehabilitation

Establishments

- Private Means

- Not Suitable

- Are suitable however require much improvement

- Suitable and require slight improvement

- Completely Suitable for my use

Individual

Individual

18. Were you satisfied with the Rehabilitation Process given to you by the service including the proficiency of Doctors and Therapists

19. Have you sought any Private Rehabilitation Services/Health Care Services for better recovery

20. If you compare the rehabilitation process given to you in the services with that of civilian establishments, how would you rate it on a linear scale Improvement Extremely

21. Relevance of First Aid during your Injury: (This question is aimed at evaluating whether the current combat casualty care practices and teachings in the service are enough or whether they require re-evaluation including modernisation of equipment and increased focus on Tactical Combat Casualty Care)

22. If given a choice, would you like to continue to serve in the Forces after the injury?

23. Do you feel the environment is more sympathetic or empathetic towards War Wounded Soldiers?

24. Were you faced with any kind of stress, particularly Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after your injury?

Answers sought on a linear scale from 1 to 10

- Not Satisfied - 1

- Extremely Satisfied - 10

- Yes

- No

Answers sought on a linear scale from 1 to 10

- Not at Par with Civilian Establishments and needs much Satisfied - 1

- At Par with Civilian Establishments - 10

- Yes - Timely First Aid and Evacuation helped me in reducing the extent of my injury

- No - The first aid and evacuation could have been better

- Maybe - One out of the Two requirements i.e., First Aid and Evacuation was not as it should have been

- Yes

- No

- Maybe

Answers sought on a linear scale from 1 to 10

- Sympathetic - 1

- Empathetic - 10

- Yes

- No

- Maybe

25. If any kind of Stress was faced, can that be quantified on a linear scale

26. Do you feel that Psychological Rehabilitation/Mental Strengthening Practices are equally important for War Wounded Soldiers to overcome any stresses they face after sustaining injuries?

27. Do you feel that certain facilities and policies may be accorded to the families or wounded soldiers during their rehabilitation. Multiple Checkboxes are mentioned, these may be selected as per choice?

28. Recommendations (in detail if any) (This part of the questionnaire is particularly important as it would help me in understanding, the personal journeys and issues faced in Rehabilitation or even the good things which you may have encountered during your road to recovery. These may include any recommendations to enhance or improve the rehabilitation process)

Answers sought on a

linear scale from 1 to 10

- Very Little Stress - 1

- Extreme Stress - 10

- Yes

- No

- Maybe

- Travel by Air for Self and Family

- Support by a Buddy provisioned by the Unit/Formation

- Regular Counselling

- Regular visits by your Unit/Formation personnel

- Accommodation Support in the Station of Rehabilitation

- Training/Counselling for Transitioning into regular life outside service

Individual

Appendix ‘B’

Analysis Of Data from Questionnaire

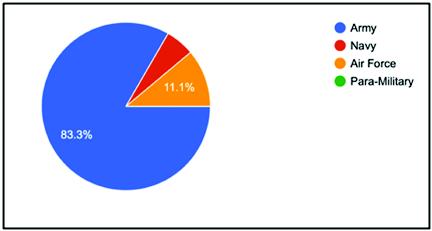

Figure 3: Services of Respondents

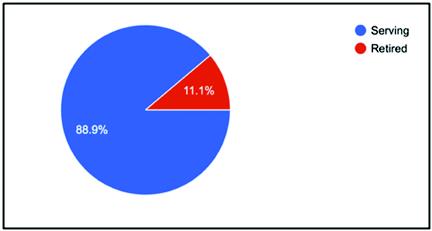

Figure 4: Serving or Retired

Figure 5: Married or Single

Figure 6: Having Children during time of Injury

Figure 7: Stress on a Linear Scale from 1 to 10

Figure 8: Satisfaction on a Linear Scale from 1 to 10

Figure 9: Sought Private Rehab Procedures

Figure 10: Would you continue to Serve

Figure 11: Relevance of First Aid during Injury

Figure 12: Did you Face Stress during Recovery

Appendix ‘C’

US Army-Amputee Care Schematic and Flowchart

Endnotes

1 ‘Duty, Honour, Country’ Address by Gen Douglas MacArthur at West Point in 1962.

2 Defence National Rehabilitation Centre. Available at: - dnrc.org.uk

3 Army Order “AO/5/2020

4 DGAFMS Medical Memorandum No. 203 – Artificial Limbs dated 2022

5 Promoting Successful Integration - Borden Institute of Medicine (US Army)

6 ‘Borden Institute’ – US Army Institute

7 ‘DNRC | Repairing Our Seriously Wounded’.- United Kingdom

8 ‘Borden Institute’ – Care for the Combat Amputee

Commander Anirudh K Singh was commissioned into the Indian Navy in 2011 and is an alumnus of Rashtriya Indian Military College-Dehradun, National Defence Academy, Pune, and Defence Services Staff College. A Marine Commando Officer, he has served in Marine Commando Force operational units in Mumbai and Visakhapatnam, specializing in airborne operations, procurement, and SOP formulation. He has also been the Diving Officer on INS Vikramaditya and Executive Officer on INS Kirch. Currently, he is Commander (Special Operations and Diving) at Naval Headquarters, New Delhi. This is the reproduction of the winning entry from the War-Wounded Foundation Joint Essay Competition.

Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CLIV, No. 638, October-December 2024

Author : Commander Anirudh K Singh

Category : Journal

Pages : 711 | Price : ₹CLIV/638 | Year of Publication : October 2024-December 2024